+38Kontinente:EUAS

+38Kontinente:EUAS1. Lebendfotos

1.1. Falter

2. Diagnose

2.1. Männchen

2.2. Weibchen

2.3. Genitalien

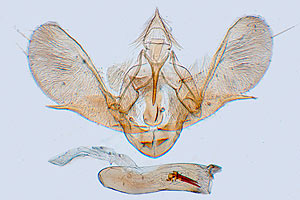

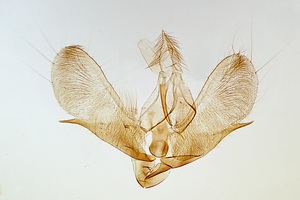

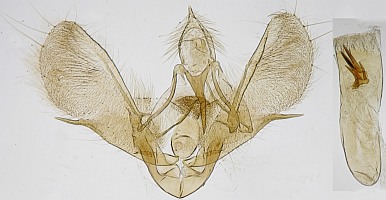

2.3.1. Männchen

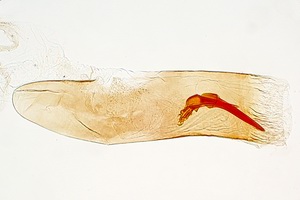

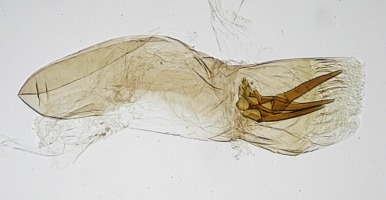

2.3.2. Weibchen

Die folgenden Bilder wurden am 18. November 2009 im Zusammenhang mit einer laufenden Diskussion eingestellt. Das Layout ist als vorläufig zu betrachten.

2.4. Weibchen_

2-3: Österreich, Niederösterreich, Schwarzau am Steinfeld, 4. Juni 2003, Präp. Nr. 1015 bzw. 396 (Präparation & Fotos: Peter Buchner) det. Peter Buchner

2.5. Männchen_

2-4: Österreich, Niederösterreich, Schwarzau am Steinfeld (Präparation & Fotos: Peter Buchner) det. Peter Buchner; [2]: 25. Mai 2003, Präp. Nr. 1014, [3]: 31. Mai 2003, Präp. Nr. 1013, [4]: 19. Juni 2003, Präp. Nr. 401

2.6. Erstbeschreibung

3. Biologie

3.1. Nahrung der Raupe

Strenggenommen noch unbekannt; aus Zuchtbeobachtungen ist zu schließen, dass sich die Raupe auch im Freiland von Moosen unterschiedlicher Familien ernährt.

Heckford (2009) fasst den Kenntnisstand zusammen: "Bland was apparently the first to have noted the larva in the wild when he found one in 1986 feeding on the superficial layers at the base of the stem and upper part of the root-stock of Valeriana officinalis L. Unfortunately, as he acknowledged, he made no larval description (Bland, 1987: 40–41). It was not until 2004 that the final instar was described (Smith, 2004: 103–107; Heckford & Sterling, 2004: 148–151) from larvae found amongst various species of moss, with Smith providing both photographs and a figure of the larva."

Er berichtet dann über eine eigene ex-ovo-Zucht, bei der zunächst nur das Goldene Frauenhaarmoos (= Gewöhnliches Widertonmoos, Polytrichum commune) gereicht wurde: "In their first instar, when they were offered only Polytrichum commune, the larvae spun some fine silken strands at the junctions of the stems and the leaves of this moss, which appeared to serve as ‘cushions’, and curled up on These strands when not feeding. Often there were several larvae to each moss stem but no more than one larva rested on the silken strands at any one junction of stem and leaves. Although parts of the strands touched both the stem and upper surface of the leaves, the larvae did not attach themselves to either substrate. Seen without magnification the larvae appeared to be suspended in mid-air above the leaves. This habit of resting on a ‘cushion’ of fine silken strands on the leaves and with several larvae to a stem continued into the second instar."

Heckford (2009) schreibt weiter: "In their early instars the larvae ate only the leaves of the moss, producing pale greenish or yellowish granular frass, which in later instars became reddish brown. As they grew the larvae were offered the mosses Rhytidiadelphus loreus (Hedw.) Warnst. and Dicranum scoparium Hedw. as well as Polytrichum commune, and also fragments of dead fronds of Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn, which were all plants and material amongst which I had found larvae previously in Devon, England. The larvae readily ate all the mosses, including the stems of Polytrichum commune and Dicranum scoparium, but none of the fragments of Pteridium aquilinum."

(Autor: Erwin Rennwald)

4. Weitere Informationen

4.1. Etymologie (Namenserklärung)

„ambiguus zweifelhaft.“

4.2. Andere Kombinationen

- Hercyna ambigualis Treitschke, 1829 [Originalkombination]

4.3. Synonyme

- Scoparia klinckowstroemi Hamfelt, 1917

4.4. Literatur

- Heckford, R.J. (2009): Notes on the early stages of Scoparia ambigualis (Treitschke, 1829) and Eudonia pallida (Curtis, 1827) (Lepidoptera: Pyralidae). — Entomologist's Gazette, 60: 221-231. [PDF auf devonmoths.org.uk]

- Erstbeschreibung: Treitschke, F. (1829): Die Schmetterlinge von Europa 7: I-VI, 1-252. Leipzig (Gerhard Fleischer).